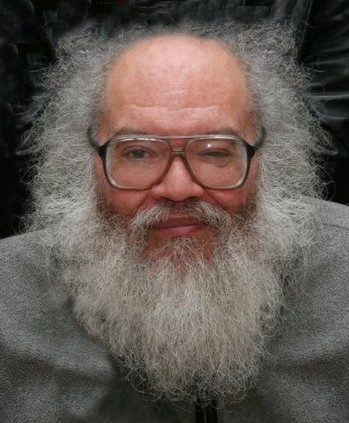

Remembering Charles Saunders (1946-2020)

By George Elliott Clarke

Africadia—Black Nova Scotia—is more beautiful than we know. Charles R. Saunders had lived in Ottawa, 15 years, 1970-1985, before he set foot in Africadia. And once he did, he only left so he could pack his Ottawa suitcase and return to the only place that he could ever again call home: Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Charles (he never went by “Chuck”) left his home city, Philly, PA, U.S.A., in 1970 so he wouldn’t have to go off to Vietnam to kill—or be killed by—folks who’d never used the “n-word” to describe black people.

In 60s parlance, Charles was a “draft-dodger.” No he weren’t! He be an anti-Vietnam War “Conscientious Objector”—like Muhammad Ali.

So, he escaped to Canada, to Ottawa—Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s Ottawa—which welcomed him. (Canada accepted 10,000, Yank, Vietnam-War refuseniks.)

There he lived for 15 years, typing up short stories, tapping out radio plays, doing journalism, and also beginning to imagine an African hero—Imaro—who many would connect to Tarzan. But Imaro was more like Nat Turner.

In fact, Imaro belonged to the Fantasy genre—a novel form that falls between sci-fi and sword-and-sandal capers. The first novel, named for the eponymous hero, appeared in 1981.

Imaro battles devilish wizards and jealous (toady lizard) rivals to win his black queen. Just as importantly, he must face down the “Mizungus”—pale people (Caucasian/European)—who want to exploit Black Africans as slaves.

Saunders published two more Imaro novels, in 1984 and 1985. And they were popular enough instantly, that Imaro II got translated into Parisian French in 1986.

By accident, I returned to Halifax in late May 1985—at the same time that Charles relocated to Africadia from Ottawa. Indeed, we met, Charles and me, in the Gottingen Street offices of The Jet Journal, presided over by future NSNDP cabinet minister, Hon. Percy Paris.

Soon, I was dropping by—regularly—his one-room abode in a Hollis Street (@ Terminal Road) rooming-house. He had a hot-plate to cook on, maybe a tiny fridge. His table was his desk, occupied by book stacks and a typewriter, and hardly any space for dishes and cutlery.

His “wallpaper” was compelling—featuring black/African women—nude—scissored out of National Geographic mags. (It was hard to talk with Charles without my eyes wandering over that colourful collage of hypnotizing pulchritude.)

I shared poetry with him; he shared short stories, screenplays, and radio plays with me. We’d give each other helpful criticism. In fact, next to Walter Borden—actor, poet, playwright, editor—Saunders was the first black professional writer I ever met.

Soon, Saunders had written radio plays for CBC Halifax and the Maritimes, focussing on boxers: The Africadians George Dixon (“Kid Chocolate”) and Sam Langford (“the Boston Tar-Baby”).

In summer 1986, Charles married Dale Farmer, and I was one of his ushers at the Cornwallis Street (now New Horizons) Baptist Church ceremony. Dale was gorgeous—in a white gown with a bouquet of red roses; Charles—all 6-feet-plus of him—was a tuxedo’d, gentle giant.

(I still have the brass razor-handle that was my official gift as an usher.)

After Charles and Dale wed, I’d drop by their townhouse (I think it was), and Charles and I continued to discuss poetry and our publications.

In 1986-87, Charles’ fortunes improved financially too: Imaro movie rights got sold to an Argentinian producer, and a Spanish-language action-flick was filmed featuring a white Imaro (sorta like Conan the Barbarian).

Charles and Dale flew south to Argentina to check out the film set, and Charles—that humble hulk of a bro, got himself photographed—grinning—trapped in a kinda stocks.

He was the first Africadian to have a movie made based on his writings.

In that same year, 1986-87, I produced—with the help of the Black United Front—a North End Halifax-based newspaper, The Rap, for which Charles wrote some articles, helping me out charitably, and giving him a space to talk about people he’d come to know and love and marry into, namely, the Africadians.

Although I hung out with Charles for only 2 years, 1985-87, when I left Halifax to go to work for Dr. Howard McCurdy, Ph.D.—Canada’s first black tenured professor and Canada’s second black Member of Parliament—we stayed in touch, never by e-mail, but always by old-fashioned letter, and we corresponded, usually, several times a year, between 1987-2020.

(I sent my last letter to him in summer 2020, and was astonished to not receive an answer, but, I couldn’t and wouldn’t, because he had passed away, in the privacy of his apartment, with no one to look in on him.)

Not only that, but we supported each other’s writing careers. When I left for Ottawa in 1987, I gave The Rap to Charles to edit, and I think he brought out one last issue before he decided that the paper could not be maintained.

In 1988, while working for Howard, I tried to do a column for The Daily News, in Halifax, on Africadian political doings.

But it was a conflict-of-interest in my job with Howard, and I was too far away—in Ottawa—to be effective.

So, I recommended to The Daily News that Charles take over my column. He did—and he was a supreme commentator on Africadia and Africadians.

(By the way, Charles liked the words “Africadia” and “Africadian”—and he used them—as did the late poet George Borden.)

Soon, Charles had written—and published in 1989—the best piece of creative non-fiction on the Africville Clearance (let’s not call it “Relocation”).

“A Visit to Africville,” based on interviews with former residents, takes us on a walking tour of Africville, in 1959, wherein the narrator guides us round the black hamlet-on-the-harbour, pointing out various homes and landmarks, and talks up local history, such as the truth that Duke Ellington would drop in on his “in-laws” in “the Ville” whenever he was stopped over in Halifax.

(I reprinted “A Visit to Africville” in my edited, historic, two-volume anthology of Africadian writing, Fire on the Water [1991-92].)

In 1990, Charles published a well-received history of Africadian pugilists, Sweat and Soul, wherein, suddenly, he could present folks like Buddy Daye and Clyde Gray and Dave Downey and Trevor Berbick as, not only, boxing champs, but as champs of social progress too.)

That same year, Charles reviewed my second book of poetry, Whylah Falls, pronouncing it “a work of genius” (I blush—invisibly), and I sure hope still that he was—and is—correct in that assessment!

Asked to write an official history of The Nova Scotia Home for Coloured Children, published as Share and Care in 1994, Charles asked me to pen a few poems to accompany his chapters, and I did.

His prose and my lyrics present a positive portrait of the Home, a decade-plus before ex-residents (or inmates) began to tell of abuse and horror, practices similar to those of other institutions wherein adults exercise total power over minors.

Charles felt guilty about not relating the full story of the Home, but, when he was researching and writing his book, there wasn’t yet testimony—or witnessing—about tortures and assaults or even any identification of perpetrators.

(To this day, in the wake of inquiries and a provincial settlement, few victims and/or victimizers have been named or detailed evidence publicized, so as to enable “healing” by suppressing vengeful attitudes and nightmarish memories.)

Charles thought that he might be called to testify at an inquiry, but he never was. If he had been called, he would have said that he wrote only about what he could cull from archives and interviews, and he did not encounter reports of evils.

Throughout the 1990s and into the Twenty-Teens, Charles produced his must-read column, becoming the expert on Bluenose anti-black racism, on Africadian politics, history, and culture, and on African Diasporic issues (such as the O.J. Simpson trial and acquittal).

His insights were always superb, moral, righteous (in the slang sense, not self-righteous), and indispensable.

Want proof? Pick up Black and Bluenose: The Contemporary History of a Community (1999).

I’d suggested to Charles that he collect his Daily News columns into a book, and then he requested that I pen the introduction: “On Charles Saunders, or The Artist as Journalist.”

Since October 1987, I’ve lived “abroad” from Nova Scotia/Africadia—in Ottawa, Kingston (Ontario), Durham (North Carolina), Montreal, Toronto, and Cambridge (Massachusetts).

But I’ve received lots of invitations to come back and speak and/or give poetry readings and/or to see a play or an opera produced.

It was only now-and-then that I’d see Charles. Indeed, the last time was the opening night of my last play, Settling Africville, September 20, 2014, at Alderney Landing Theatre.

It was a full house—and a very exciting night—and the applause was rapturous: A thunderous, standing ovation. Hurrah!

But one of the nicest things about the event was seeing Charles, with a girlfriend—a Swiss lady (he and Dale had long been divorced by this time)—though we had only nanoseconds to talk.

But there he was: As imposing as a standing bear, as friendly as a Great Dane.

We’d shake hands, but he’d also give me a terrific, welcoming bear-hug. He always had my back, and was my intellectual anchor regarding Africadian goings-on and characters.

So, I was surprised last summer when I had no answer for my latest letter to him.

And then I was shocked, in December 2020, to learn that my long-time friend had died, alone, and then been buried in an unmarked grave—even though he was in the midst of discussions to see Imaro filmed by an African-American director (which must have been a dream come true for him).

Journalists like Jon Tattrie did vital service and gave correct homage to Charles, but still—in my opinion—failed to give any sense of the full scope of Charles’s achievement as journalist, historian, novelist, and screenwriter over 35 years.

35 years! Think about that.

In fact, we Africadians—Indigenous Blacks, African-Nova Scotians, Scotians—do not honour enough our Intellectuals and Artists.

We prefer to celebrate preachers and boxers—and singers, but not—so much—musicians, actors, dancers, composers, sculptors, painters, filmmakers, philosophers, journalists, playwrights, poets, screenwriters, directors, scholars, etc.

High time to change up that parlous situation!

An excellent start would be for the community to come together and stage an annual reading (or dramatization) of “A Visit to Africville” and/or to enact scenes from Imaro.

We owe Charles R. Saunders a hero’s funeral, a redoubtable artist’s wake, and even posthumous recognition from the Nova Scotian government.

Good people, this is our Responsibility. See to it!

About the Writer

George Elliott Clarke is a Canadian poet, playwright and literary critic who served as the Poet Laureate of Toronto from 2012 to 2015 and as the 2016–2017 Canadian Parliamentary Poet Laureate. His work is known largely for its use of a vast range of literary and artistic traditions (both “high” and “low”), its lush physicality and its bold political substance. One of Canada’s most illustrious poets, Clarke is also known for chronicling the experience and history of the Black Canadian communities of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, creating a cultural geography that he has coined “Africadia”.